Posts Tagged #behind the scenes @ the henry ford

IMLS Update: Analysis and New Tools

This blog post is part of a series about storage relocation and improvements that we are able to undertake thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

This blog post is part of a series about storage relocation and improvements that we are able to undertake thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

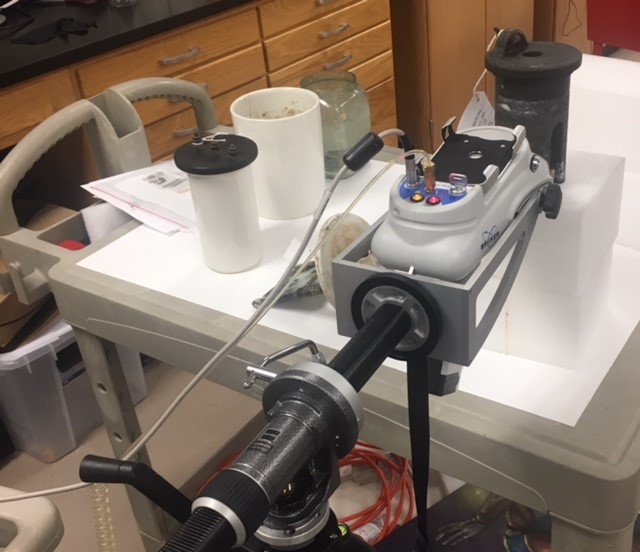

In the course of our work as conservators, we get some very exciting opportunities. Thanks to a partnership with Hitachi High Technologies, for the past few months the conservation lab here at The Henry Ford has had a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) with an energy-dispersive x-ray (EDX) spectroscopy attachment in our lab.

What does this mean? It means that not only have we been able to look at samples at huge magnifications, but we have had the ability to do elemental analysis of materials on-demand. Scanning electron microscopy uses a beam of electrons, rather than light as in optical microscopes, to investigate the surface of sample. A tungsten filament generates electrons, which are accelerated, condensed, and focused on the sample in a chamber under vacuum. There are three kinds of interactions between the beam and that sample that provide us with the information we are interested in. First, there are secondary electrons – the electron beam hits an electron in the sample, causing it to “bounce back” at the detector. These give us a 3D topographical map of the surface of the sample. Second, there are back-scattered electrons – the electron beam misses any electrons in the sample and is drawn towards a positively-charged nucleus instead. The electrons essentially orbit the nucleus, entering and then leaving the sample quickly. The heavier the nucleus, the higher that element is on the periodic table, the more electrons will be attracted to it. From this, we get a qualitative elemental map of the surface, with heavier elements appearing brighter, and lighter elements appearing darker.

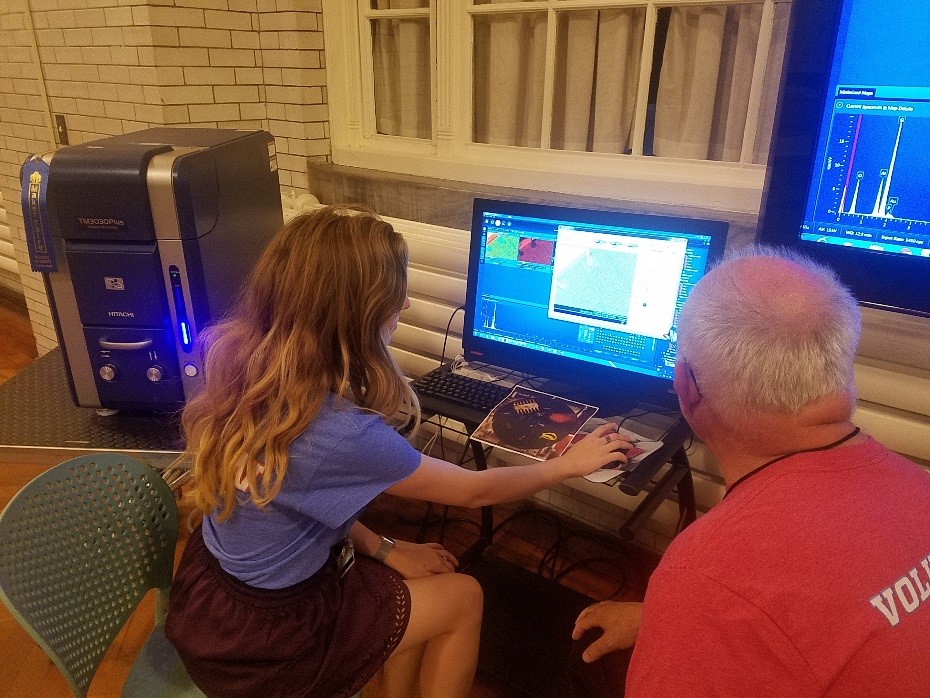

What does this mean? It means that not only have we been able to look at samples at huge magnifications, but we have had the ability to do elemental analysis of materials on-demand. Scanning electron microscopy uses a beam of electrons, rather than light as in optical microscopes, to investigate the surface of sample. A tungsten filament generates electrons, which are accelerated, condensed, and focused on the sample in a chamber under vacuum. There are three kinds of interactions between the beam and that sample that provide us with the information we are interested in. First, there are secondary electrons – the electron beam hits an electron in the sample, causing it to “bounce back” at the detector. These give us a 3D topographical map of the surface of the sample. Second, there are back-scattered electrons – the electron beam misses any electrons in the sample and is drawn towards a positively-charged nucleus instead. The electrons essentially orbit the nucleus, entering and then leaving the sample quickly. The heavier the nucleus, the higher that element is on the periodic table, the more electrons will be attracted to it. From this, we get a qualitative elemental map of the surface, with heavier elements appearing brighter, and lighter elements appearing darker.  Conservation Specialist Ellen Seidell demonstrates the SEM with Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation volunteer Pete Caldwell.

Conservation Specialist Ellen Seidell demonstrates the SEM with Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation volunteer Pete Caldwell.

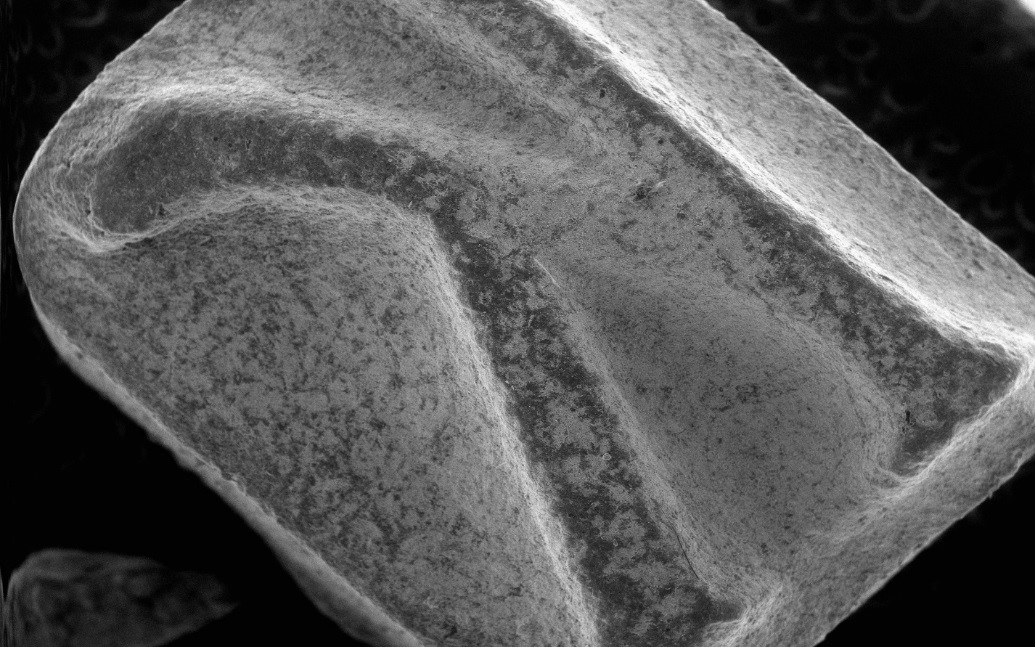

The EDX attachment to the SEM allows us to go one step further, to a third source of information. When the secondary electrons leave the sample, they leave a hole in the element’s valence shell that must be filled. An electron from a higher valence shell falls to fill it, releasing a characteristic x-ray as it does so – the detector then uses these to create a quantitative elemental map of the surface. A ‘K’ from a stamp block, as viewed in the scanning electron microscope.

A ‘K’ from a stamp block, as viewed in the scanning electron microscope.

The understanding of materials is fundamental to conservation. Before we begin working on any treatment, we use our knowledge, experience, and analytical tools such as microscopy or chemical tests to make determinations about what artifacts are made of, and from there decide on the best methods of treatment. Sometimes, materials such as metal can be difficult to positively identify, especially when they are degrading, and that is where the SEM-EDX shines. Take for example the stamp-block letter shown here. The letter was only about a quarter inch tall, and from visual inspection, it was difficult to tell if the block was made of lead (with minor corrosion) or from heavily-degraded rubber. By putting this into the SEM, it was possible a good image of the surface and also to run an elemental analysis that confirmed that it was made of lead. Knowing this, it was coated to prevent future corrosion and to make it safe to handle.

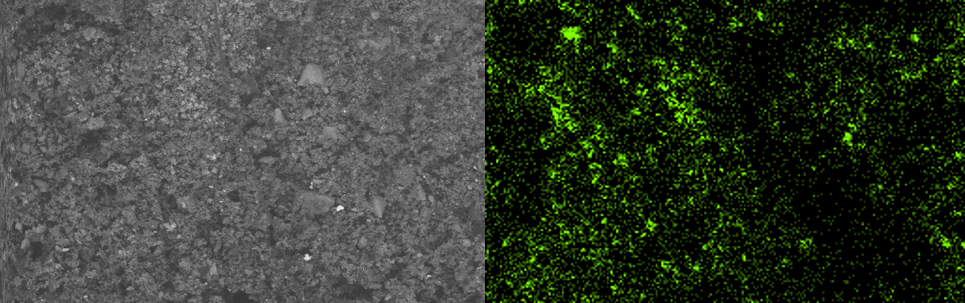

Elemental analysis is also useful when it comes to traces of chemicals left on artifacts. We recently came across a number of early pesticide applicators, which if unused would be harmless. However, early pesticides frequently contained arsenic, so our immediate concern was that they were contaminated. We were able to take a sample of surface dirt from one of the applicators and analyze it in the SEM. An SEM image of a dirt sample from an artifact (left) and a map of arsenic within that sample (right).

An SEM image of a dirt sample from an artifact (left) and a map of arsenic within that sample (right).

The image on the left is the SEM image of the dirt particles, and the image on the right is the EDX map of the locations of arsenic within the sample. Now that we know they are contaminated, we can treat them in a way that protects us as well as making the objects safe for future handling.

We have also used the SEM-EDX to analyze corrosion products, to look at metal structures, and even to analyze some of the products that we use to clean and repair artifacts. It has been a great experience for us, and we’re very thankful to Hitachi for the opportunity and to the IMLS as always for their continued support.

Louise Stewart Beck is the project conservator for The Henry Ford's IMLS storage improvement grant.

philanthropy, technology, IMLS grant, conservation, collections care, by Louise Stewart Beck, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Resourcefulness in Photography with the Collections

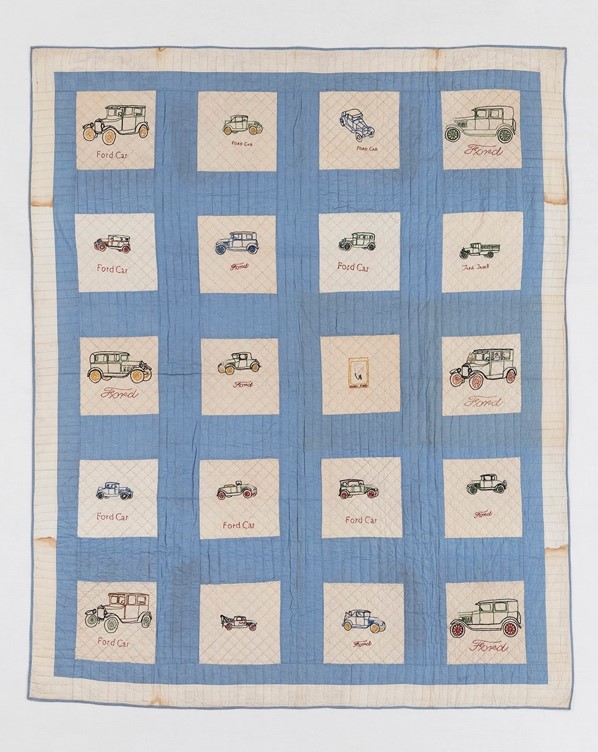

Have you ever wondered how we photograph quilts at The Henry Ford? While the answer is probably no, you might be surprised to find out that it is quite a process. Most quilts are quite large, ranging from 7ft x 4ft to even 9ft x 5ft. With that being said, our photo studio in the museum only has a ceiling that is 10ft tall, but to get an accurate picture of the quilt we would need the camera to be pointing at the quilt at a 90-degree angle. How do we accomplish that in a room that’s only 10 ft tall? We find higher ground!

Since our studio is on the back wall of the museum, we need to be somewhere elevated, but relatively nearby so we aren’t hauling our equipment all over the place. So, the Highland Park Engine is our answer. We mount the camera on the top railing of the stairs closest to the entrance to Conservation.

Then, with the help of 2-3 people, we lay the quilts on a large 10 x 10 wooden board that has a layer of muslin cloth on it (to protect the quilts and stop them from sliding down the board), We hoist the quilt board up onto stands to hold it in place at about a 60-degree angle which allows us to angle the camera to shoot straight at the quilt, giving us the correct perspective as if it were lying flat.

Here are a few examples of the finished images that go online on our Digital Collections website.

Looking at them, you wouldn’t think that they were photographed any other way than lying down, right? That’s the magic of photography - with a little bit of resourcefulness and ingenuity added in.

You can view all the quilts from our collection that we’ve photographed on our Digital Collections here.

Jillian Ferraiuolo is Digital Imaging Specialist at The Henry Ford.

Henry Ford Museum, quilts, photography, digitization, collections care, by Jillian Ferraiuolo, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Solving a Collections Mystery with IMLS

Susan Bartholomew, Collections Specialist here at The Henry Ford, is busy cataloging objects from The Henry Ford's Collections Storage Building (CSB). A three-year grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, supports conserving, rehousing, and digitizing thousands of objects currently housed in several bays of the CSB.

Susan Bartholomew, Collections Specialist here at The Henry Ford, is busy cataloging objects from The Henry Ford's Collections Storage Building (CSB). A three-year grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, supports conserving, rehousing, and digitizing thousands of objects currently housed in several bays of the CSB.

As the grant narrative explains, the IMLS funding supports a “critical element in a major institutional project: the consolidation of The Henry Ford's off site collections into a new location on campus.” The work “will improve the physical condition of the project artifacts through conservation treatment, rehousing, and removal to improved environments.” Finally, IMLS funding “will facilitate collections access through the creation of catalog records and digital images, available to all via The Henry Ford's digital collections.”

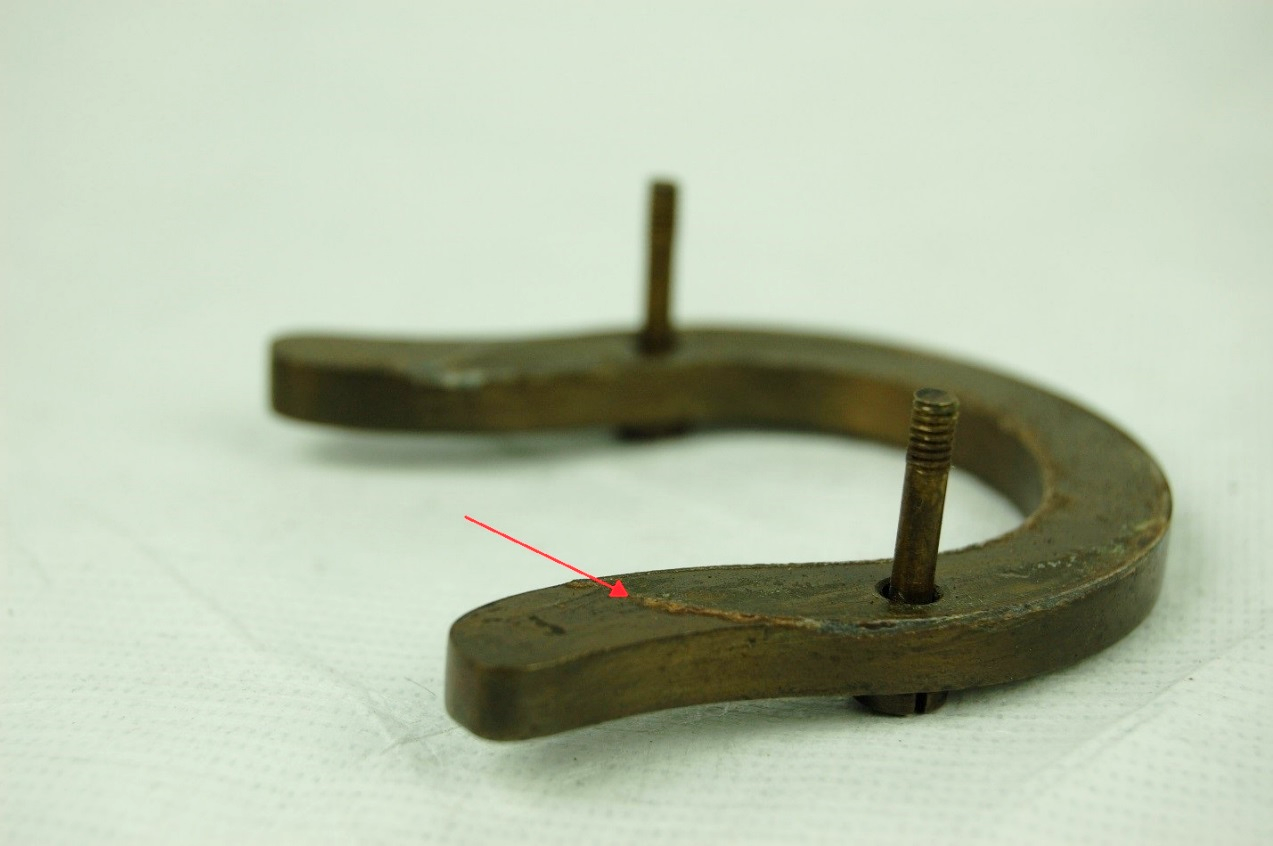

Occasionally Susan comes upon an artifact that needs additional explanation to accurately catalog it, such as this one. Here's what we knew upon examination:

- It's 16" long, 7" wide

- Has a smooth wooden handle

- Is bent and welded iron

- There's a ringed brass flange positioned to reduce wear where the metal is imbedded into the organic material.

The questions we then ask: What is this instrument? What purpose does it serve?

We turned to our horse experts with the Ford Barn team in Greenfield Village to help us understand its use.

A steady diet of oats, grass, and hay wears a horse’s teeth down as they age. Persistent grinding of food can leave sharp burrs or edges on the outside of their molars. Untreated, this causes pain when the horse chews, and they lose weight.

Farmers and veterinarians used this instrument (called a “gag” or speculum) to hold a horse’s mouth open as they floated the horse’s teeth to balance their bite. Floating helps a horse maintain a healthy bite in their senior years.

A person (farmer or veterinarian) would insert the “gag” into the horse’s mouth, holding it by the handle. Then, the farmer/veterinarian would pull downward on the handle which “encouraged” the horse’s mouth to open. The oval area provided a window through which to place the float (a rasp used to file down the sharp edges).

The device proved useful when treating younger horses with other dental issues, too. Today caring for aging horses still requires floating and balancing their teeth. Caregivers still use a speculum to hold the horse’s mouth open, and to keep their head steady during floating and balancing, but the instruments today have padding to reduce stress on the horse’s jaw during the procedure.

Thanks to the IMLS for providing the invaluable funding to help make this exploration of animal care possible.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Jim Slining is Curator of Museum Collections at Tillers International.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, IMLS grant, healthcare, farm animals, by Jim Slining, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Digging Into Mathematica

Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation is a place of wonder and inspiration, and this past March and April, it was my privilege to work with staff behind the scenes. My name is Jamison Van Andel, and I am an 11th-grade student at Henry Ford Academy. As part of the school’s curriculum, students are expected to complete a six-week internship with a local organization. While searching for an internship placement, I contacted The Henry Ford in hopes that a curator would be willing to work with me. A history aficionado, I had fallen in love with The Henry Ford and was overwhelmingly curious about the work that goes into a curator’s day-to-day experience.

Dr. Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication and Information Technology, responded with a project. The Mathematica exhibit, a recent addition to the museum floor, was in need of some background research to improve its representation of diverse mathematicians. I was thrilled to tackle the challenge.

Going into my first week of work, I imagined that curators worked in secluded offices, reading and researching various subjects individually. In actuality, curatorial research is a highly collaborative process. As I met several curators, it became clear that they all bounce ideas off each other as they conduct research.

As I completed more and more research, Dr. Gallerneaux introduced me to the art of writing narratives--capsules of information about an object or topic, in 60 words or less. A delicate exercise, narrative writing requires the author to communicate lots of information on in a terse, but erudite fashion. I found this was especially difficult when I had spent a great deal of time with a subject, because every discovery of my research seemed incredibly meaningful in my eyes.

I’m quite fond of the following narrative, largely because Artur Avila was a fun character to research, but also due to the fact that I believe I was able to capture the cultural significance of his achievements as well as their mathematical implications:

Along with his easygoing persona, Artur Avila is known for his remarkable ability to clarify very complex material. Avila, a Fields Medalist in 2014, holds citizenship in both his native Brazil and France. He has become an ambassador for Brazilian mathematicians, working in the dynamical systems field that analyzes the correlation between time and geometrical position of a point.

Later, I composed a narrative about the International Mathematical Olympiad after noting that several of the mathematicians I researched had participated in it. This was an entertaining exercise for me, as many of the Olympiad competitors are close to my own age. Curators often face the challenge of making subjects compelling for all museum guests, and it helps to have several connection points within an exhibit that pertain to different groups. In this case, a narrative about teenage mathematicians might serve as common ground with current-day students.

The International Mathematical Olympiad is the premier contest for high school mathematicians. Held yearly in different countries, the Olympiad invites six-person teams from over 100 countries to participate. Each student individually constructs answers to six problems, with content ranging from complicated algebra to number theory. Winners may receive a gold, silver, or bronze medal as well as an honorable mention.

Besides the research and narrative writing, I was able to attend several curatorial meetings. One particular gathering, a Collections Committee meeting, was especially entertaining. Twice a month, the curatorial team meets to determine what artifacts are to be added to the collection. Humorous, engaging, and thought-provoking, the meeting was the epitome of curatorial work at The Henry Ford. I left with a concrete idea of the qualities an artifact must have in order to fit into a museum’s mission.

After compiling a portfolio of 20 narratives, I arranged them in a digital platform that serves as a prototype for a future digital project that will support the interpretation of the Mathematica exhibit. The capstone project of my internship, it presents the narratives in an interactive way for guests to experience, similar to many of the digital resources currently on the museum floor. For now, the finished narratives will be stored in the museum’s database for future implementation, with the eventual goal that guests will be able to interact with this information.

An absolutely unforgettable experience, the internship gave me an extensive, behind-the-scenes look at the inner workings of a world-class museum. The intentionality with which everything was done was remarkable to someone who often only sees the finished product. It was an honor to work beside the masterminds responsible for making The Henry Ford the wonderful, inspirational place that it is.

Jamison Van Andel is an 11th Grade student at Henry Ford Academy.

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, education, research, Henry Ford Museum, by Jamison Van Andel

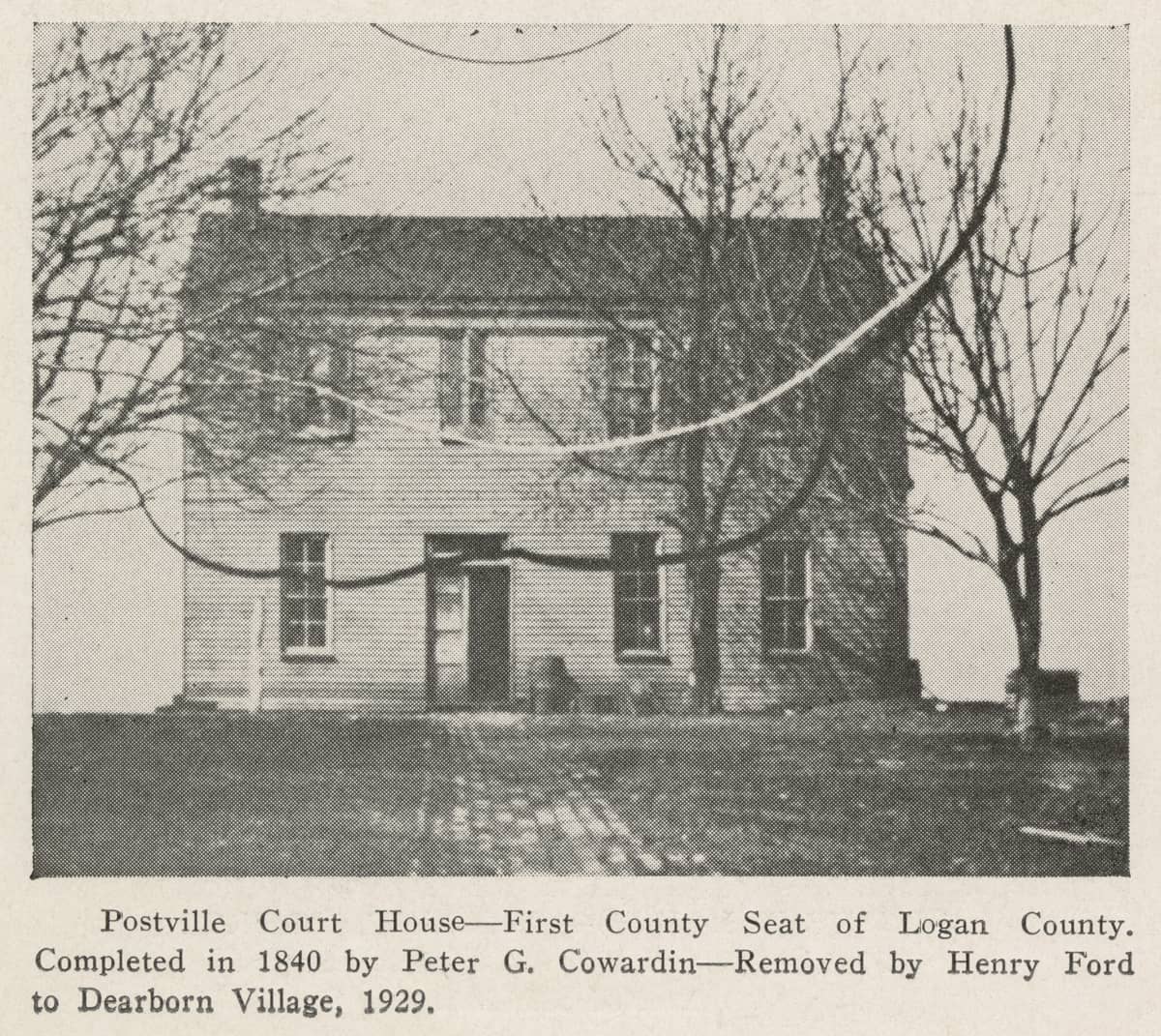

The Logan County Courthouse, a fixture on the Village Green in Greenfield Village, will has reached the milestone of having been here in Dearborn for as many years as it was in Postville, Illinois - 89 years.

Abraham Lincoln featured prominently in Henry Ford’s plans for Greenfield Village, which revolved around the story of how everyday people with humble beginnings would go on to play important roles in American history. Lincoln epitomized Ford’s view of the “self-made man,” and he made a significant effort to collect as many objects as possible associated with him. By the late 1920s, Henry Ford was a “later comer” to the Lincoln collecting world, but with significant resources at his disposal, he did manage to secure a few very important items. The Logan County Courthouse is among them.

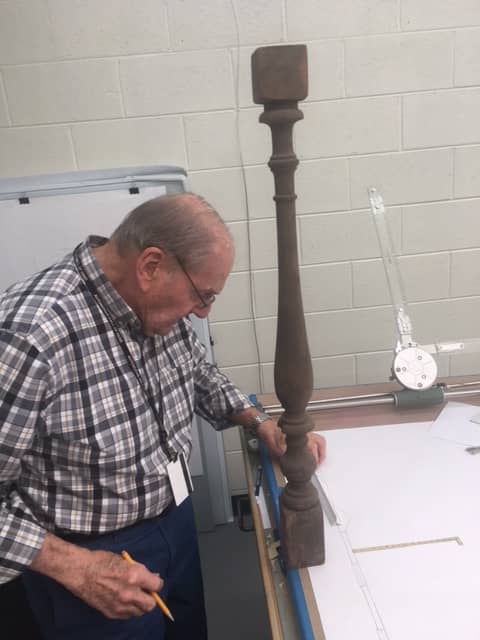

It has taken nearly all the 89 years to achieve this, but an original feature, long absent from the courtroom is making a return. The bar now stands again. Using the original set of spindles, we have re-created our interpretation of what the rail, or the bar, that divided the courtroom may have looked like in the1840s. By referencing images of other early 19th century courtrooms, and studying architectural features represented in Greenfield Village, a typical design was created.

The stories associated with the Logan County Courthouse are fascinating. As it turns out, the story of how the original spindles from the original bar finally made their way back into the courthouse is fascinating as well.

Authenticated objects, related to Lincoln’s early life, were especially scarce by the late 1920s. There seemed to be an abundance of items supposedly associated and attributed to Lincoln, especially split rails and things made from them, but very few of these were the real thing. For Ford, the idea of acquiring an actual building directly tied to Lincoln seemed unlikely.

But, by the summer of 1929, through a local connection, Ford was made aware that the old 1840 Postville/Logan County, Illinois courthouse, where Lincoln practiced law, was available for sale. The 89-year-old building was used as a rented private dwelling, and was in very run-down condition, described by some as “derelict.” It was owned by the elderly Judge Timothy Beach and his wife. They were fully aware of the building’s storied history, and had made several unsuccessful attempts to turn the historic building over to Logan County in return for taking over the care of the building. Seeing no other options, the Beaches agreed to the sale of the building to Ford via one of his agents. They initially seemed unaware of Ford’s intentions to move the building to Greenfield Village, assuming it was to be restored on-site much like another historic properties Ford had taken over. This image shows the state of the building when it was first seen by Henry Ford’s staff in late August of 1929. Not visible in the large shed attached to the rear of the building. THF238386

This image shows the state of the building when it was first seen by Henry Ford’s staff in late August of 1929. Not visible in the large shed attached to the rear of the building. THF238386

The local newspaper, The Courier, even quoted Mrs. Beach as stating that, “she would refund to Mr. Ford if it was his plan to take the building away from Lincoln, as nothing was said by the agent about removal”. By late August of 1929, the entire project in West Lincoln, Illinois, had captured the national spotlight and the old courthouse suddenly had garnered a huge amount of attention, even becoming a tourist destination. By early September, local resistance to its removal was growing, and Ford felt the need to pay a visit to personally inspect the building and meet with local officials, and the Beaches. He clearly made his case with the owners and finalized the deal. As reported, “Ford sympathized with the sentiment of the community but thought that the citizens should look at the matter from a broader viewpoint. He spoke for the cooperation of the community with him in making a perpetual memorial for the town at Dearborn, where the world would witness it. My only desire is to square my own conscience with what I think will be for the greatest good to the greatest number of people."

Henry had made his case and the courthouse would indeed be leaving West Lincoln. Immediately following the final negotiations, Henry Ford’s crew arrived to begin the process of study, dismantling, and packing for the trip to Dearborn. Local resistance to the move continued as the final paperwork was filed to purchase the land. By September 11, the resistance had run its course and the dismantling process began. It was also revealed that the city, county, several local organizations, and even the state of Illinois had all been offered several opportunities to acquire the building and take actions to preserve it. They all had declined the various offers over the years. It was then understood that Judge & Mrs. Beach, in the end, had acted on what was best for the historic building and should not be “subjected to criticism.” Judge Beach would die on September 19, just as the last bits of the old courthouse were being loaded for their journey to Greenfield Village.

Reconstruction, which included the fabrication of many of the first-floor details and a new stone chimney and fireplaces, began immediately. In roughly a month’s time, the building was ready for the grand opening of Greenfield Village on October 21, 1929.

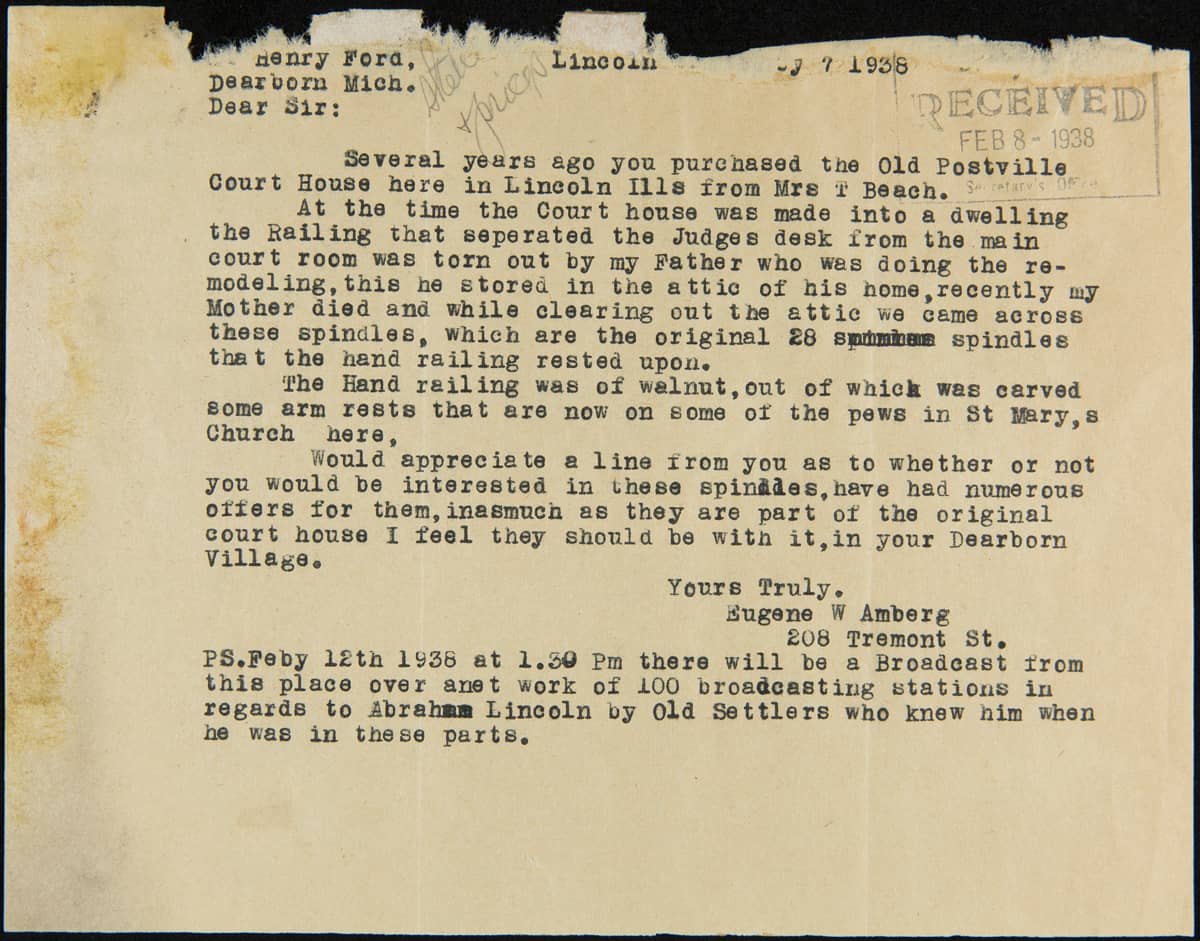

Nine years later, in 1938, Eugene Amberg sent a letter to Ford describing an interesting discovery. Mr. Amberg was a native of what was now Lincoln, Illinois and worked as a railroad ticket agent. He had a great interest in the local history and was a collector of local artifacts. As he writes in the letter dated February 8, 1938:

Several years ago, you purchased the Old Postville Court House here in Lincoln, Ills from Mrs. T Beach. At the time the Court House was made into a dwelling the railing that separated the judges desk from the main court room was torn out by my father (John Amberg) who was doing the remodeling, this he stored in the attic of his home, recently my mother died and while cleaning out the attic we came across these spindles, which are the original 28 spindles that the hand railing rested upon. The hand railing was of walnut, out of which was carved some arm rests that are now on some of the pews in St. Mary’s, a church here.

Would appreciate a line from you as to whether or not you would be interested in these spindles, have had numerous offers for them, inasmuch as they are part of the original court house I feel they should be with it, in your Dearborn Village.

Dated February 7, 1938, this is the initial letter from Gene Amberg to Henry Ford offering the 28 original spindles for sale. Despite several letters back and forth, a price could not be settled upon, and the transaction never took place. THF288006

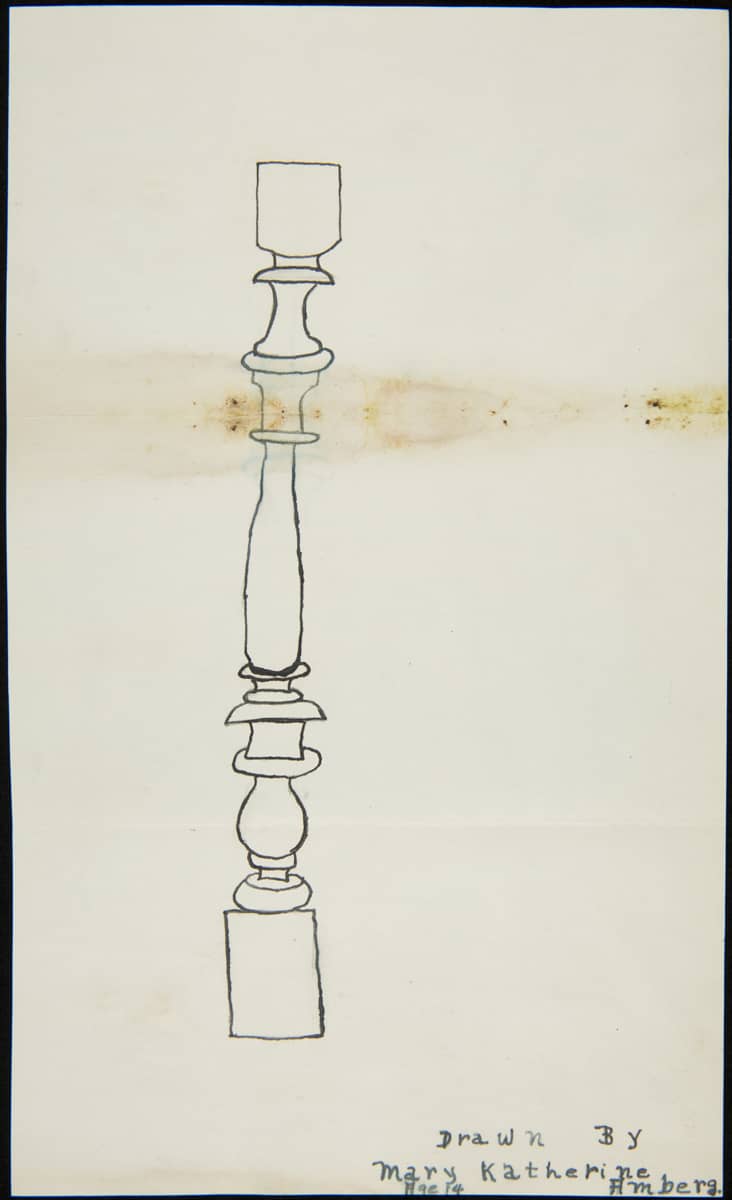

This drawing was sent by Gene Amberg, as a follow-up to his first letter offering the spindles for sale. The artist, Mary Katherine, was Gene’s 14 year old daughter. THF288012

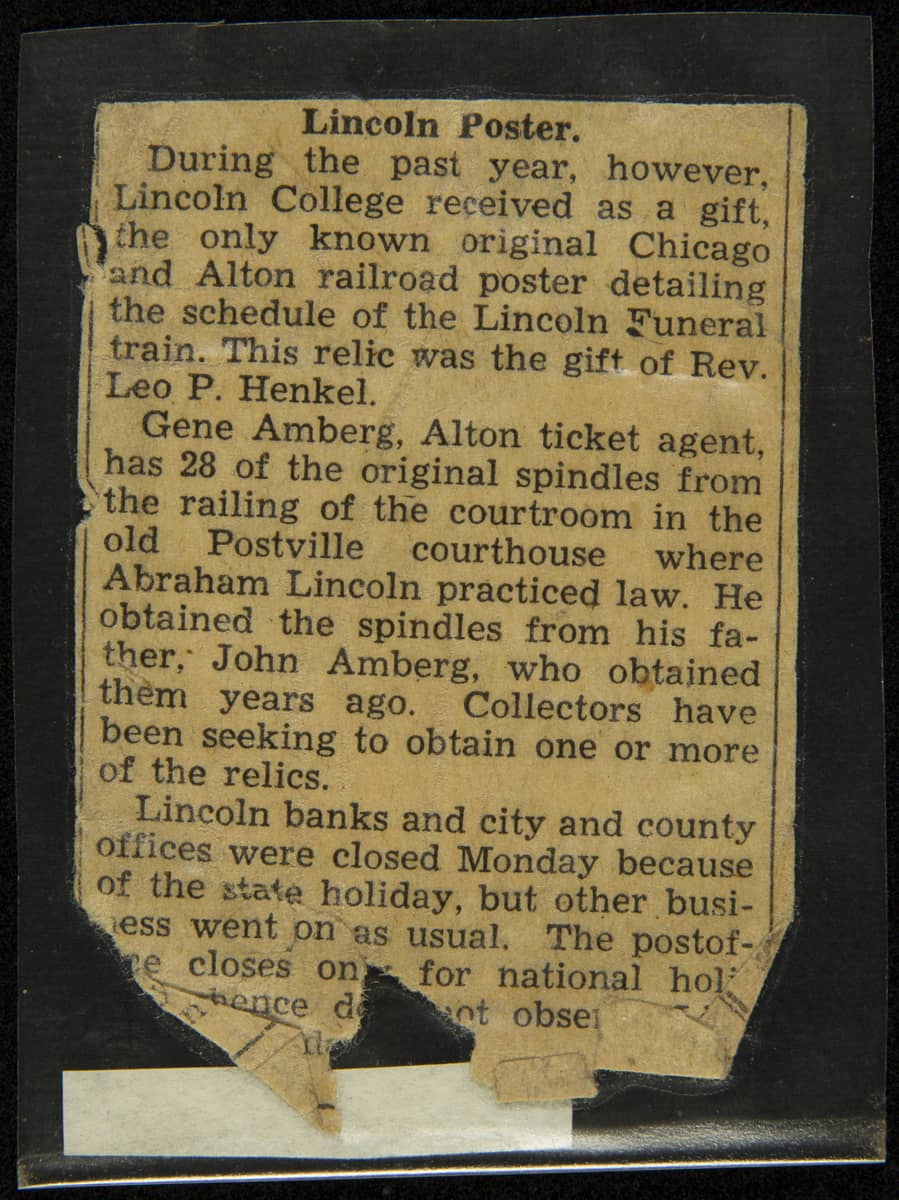

Negotiations evidently faltered, as a price was not agreed upon, and the spindles were never sent. Fast forward 71 years to 2009 when an email arrived from Carol Moore and her brother, Dennis Cunningham, the grandchildren of Eugene Amberg. They had no idea that their grandfather had begun this process, and were amazed when we produced the original correspondence from our archival collection. As it turns out, their story was almost identical to Eugene’s. As Carol wrote their mother, “Patricia Amberg Cunningham died March 1, 2008. While cleaning her house in Delavan, Illinois to prepare for sale, we found 28 old wooden spindles and a newspaper article believed to be from the Lincoln Courier indicating that the spindles are from the original Postville Courthouse in Lincoln, Illinois. It is our desire to donate them to the original Postville Courthouse.”

She was very familiar with Greenfield Village, and had visited the courthouse here. Jim McCabe, the Buildings Curator at the time, gladly accepted the donation.

Clipping from the Lincoln Courier ca. 1934, noting the 28 spindles from the “old Postville courthouse” in the possession of Gene Amberg. THF288016, THF288017

In 1848, the county seat moved from Postville, to Mount Pulaski. At that time the courthouse was decommissioned, and the county offices moved to a new courthouse. After a legal battle between the County, and the original investor/builders of the building, it was sold to Solomon Kahn. None other than Abraham Lincoln successfully represented the County in the matter.

Understanding the local history helps to also understand the changes that took place to the building. It explains how and why portions of the building were altered, parts removed, and eventually separated.

By the late 1840s, changes had taken place on both the exterior and interior. The most significant of these was the move off its original foundation, 86 feet forward on the lot. Mr. Kahn converted the building into a general store, and ran the local post office. It was he who moved the building to its new location. In doing so, it was lifted off its original limestone foundation, and the original single limestone chimney and interior fireplaces were demolished. A new brick lined cellar and foundation were created, along with updated internal brick chimneys on each end of the building, designed to accommodate cast-iron heating stoves.

This is the earliest known photograph of the Logan County Courthouse taken some time between 1850 and 1880. This photograph shows the building in its second location, 80 feet forward from its original foundation, at the crest of a small rise. The original window and door configuration remain intact. The original single stone chimney, now restored to the left side of the building, has been replaced by two internal brick chimneys designed for cast-iron heating stoves. Though not visible in the photograph, the building now sits on a new brick foundation and cellar. The items sitting near the doorway speak to the building’s new life as a store. THF132074

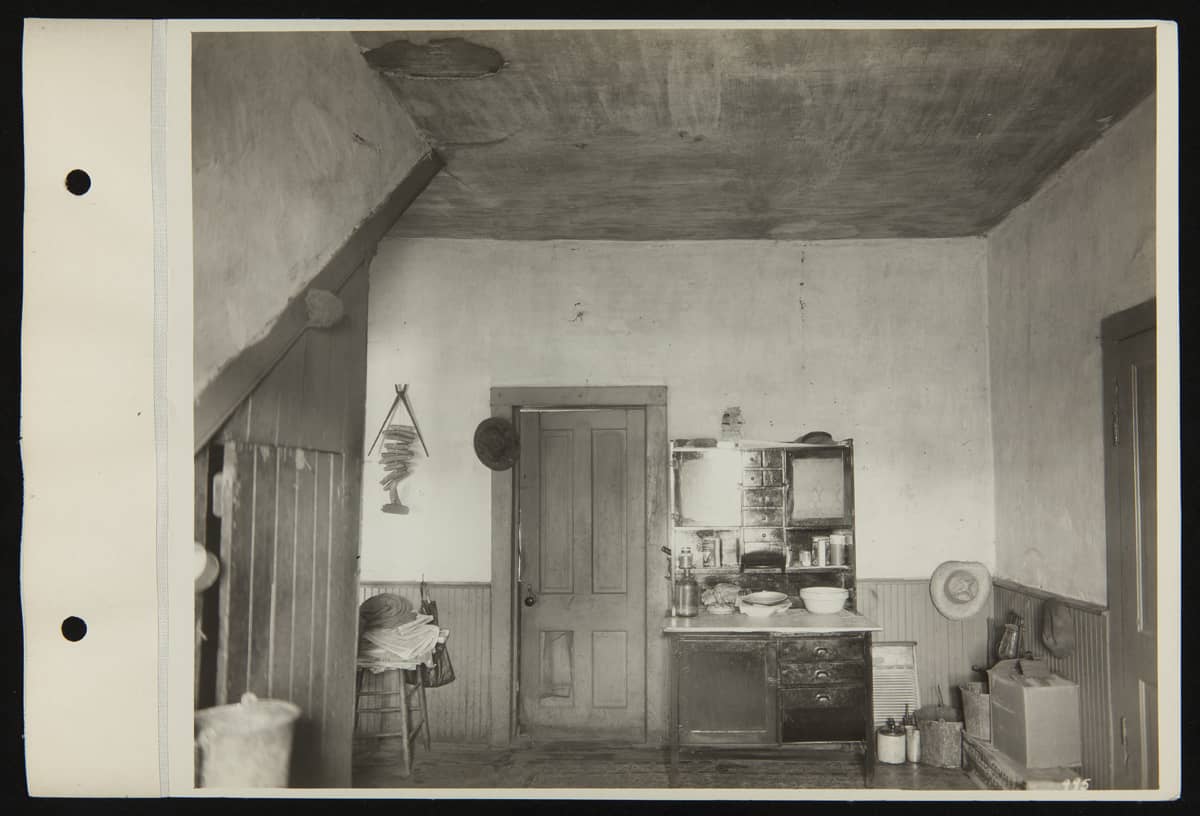

By 1880, the old courthouse had been converted from a commercial building into a private dwelling, and that was the state in which it was found by Ford’s crew in 1929. The doorway and first floor interior had been radically changed. Later, a porch was added to the front entrance, and a shed addition was added to the rear. Photographs taken in September of 1929 during the dismantling, show the outline of the original chimney on the side of the building where it has been re-created today. Further discoveries revealed the original floor plan of a large single room on the first-floor, and the original framing for the room divisions on the second. Second floor photographs show the original wall studs, baseboards, chair rails, window, and door frames, all directly attached to the framing, with lath and plaster added after the fact. The framing of the walls on the first floor were all clearly added after the original build.

This post 1880 view of the Logan County Courthouse shows its transformation into a two- family dwelling. Note the single doorway is now two, the second now taking the place of a former window opening. THF238350

This image shows further remodeling of the front of the building. This photo ca.1900 shows the addition of recessed covered porch with some decorative posts and millwork. This is the iteration in which the building was found when it was sold to Henry Ford in September of 1929. THF238348

These three images show the re-modeled interior of what was the original courtroom, now serving as the kitchen, dining room, and parlor. These photos were taken by Henry Ford’s staff just prior to the dismantling of the building in September of 1929. THF238580

The sub-divided first floor courtroom. THF238600

View of the cellar entrance under the stairway in the sub-divided courtroom. THF238598

We have no evidence that tells us what if any interior changes Mr. Kahn may have made when he relocated the building around 1850. The earliest photograph we have of the building shows it in its new location, but except for its new brick chimneys, it retains what appears to be its original door and window configuration. We can only assume that Mr. Kahn had kept the rail in place, which may have proved useful in the building’s new configuration as a store and post office. No photographs of the original courtroom exist and extensive changes made first in 1880, and then when the building was dismantled and reconstructed in Greenfield Village, further comprised any original evidence.

This view of the dismantled second floor shows matching trim and chair rail connected directly to the studs indicating this as the originally installed woodwork from 1840. The wall partition studs are also notched to meet the ceiling joists, showing that they are also part of the original framing configuration of the second floor. All the trim work, including the doors were made of walnut. THF285571

Based on the evidence we do have about these changes, it is very likely that at the time of the building’s conversion into a private dwelling, around 1880, the decorative hand-turned spindles and walnut hand rail would have been salvaged as the first floor of the building was sub-divided into a duplex. As stated in the family history, the walnut top rail was re-purposed and used in St. Mary’s Catholic Church (which burned in 1976), and the spindles saved for a future project.

Analysis of the original spindles showed that they were poplar, a wood commonly used for turning and as a secondary wood in the mid-19th century. Based on what we knew, we decided to use a combination of woods for the reconstruction of the bar rail. Walnut was used for the top rail and column caps, and the remainder of was done in poplar. Though refinished in 1929, the original walnut trim throughout the building was used as a guide for the color and sheen of the final finish. Reproduction hardware, again based on the existing hardware, mainly on the second floor, was used to mount the center gate.

Mose Nowland, conservation team volunteer at The Henry Ford, works on the design rendering for the bar. (Photo by Jim Johnson)

Mose Nowland and other members of The Henry Ford Conservation Team with the newly installed bar. (Photo by Bill Pagel)

The design of the physical installation of the rail and gate was robust. Each of the support columns is supported within by a steel post that runs through the floor joists and into the cellar floor. With over a half million guests visiting Greenfield Village each year, we thought this important. The design also offers some degree of protection to the original spindles that are centered within the top and bottom rail. This is a permanent installation, and we wanted to be sure it would stand up to the test of time.

Views of the newly re-created bar at the Logan County Courthouse in Greenfield Village. (Photos by Jim Johnson)

A huge thank you to Mary Fahey and Dennis Morrison for stewarding the project. Also to Mose Nowland, our extraordinary volunteer with The Henry Ford’s Conservation Team, who lead the charge in creating the design, and produced beautifully detailed drawings. Ken Gesek, one of our Historic Buildings Carpenters, built the rail, Cuong Nguyen and Tamsen Brown, with the help of the rest of the THF Conservation Team, oversaw the restoration of the original spindles. Tamsen also developed the formula to match the stain and finish to the existing woodwork in the courthouse. Jason Cagle, from the Painting Staff, skillfully applied the finish. Many other people worked to move the project forward as well.

This true team effort resulted in the original spindles finally being reunited with the Logan County Courthouse after an absence of nearly 140 years.

Logan County Courthouse as it appears today in Greenfield Village. (Photo by Jim Johnson)

Jim Johnson is Director of Greenfield Village at The Henry Ford.

Explore more of our Logan County Courthouse artifacts in our digital collections.

Sources Cited

- Fraker, Guy C. Lincoln’s Ladder to the Presidency: The Eighth Judicial Circuit, Carbondale, IL., Southern Illinois University Press, 2012.

- Leigh Henson, Mr. Lincoln, Route 66, and Other Highlights of Illinois, The Postville Courthouse as Private Property, http://findinglincolnillinois.com/sitemap.html

- Lincoln’s Eight Judicial Circuit, http://www.lookingforlinocln.com/8thcircuit/

- Logan County Courthouse Spindle Accession File, 2009.111, items 1-28, Archival Collection of the Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- Logan County Courthouse Building Files including original correspondences, records, photographs prior to dismantling in September of 1929, photographs of dismantling process, September 1929, reconstruction photographs, Greenfield Village, September 1929, 19th century photographic images, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- The Herald, vol. 5 n.3, The Edison Institute Press, March 4, 1938.

- Illinois, Logan County, Postville, 1840 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration

- Illinois, Logan County, Postville, 1850 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration

- Stringer, Lawrence B, The History of Logan County, Illinois, A Record of its Settlement, Organization, Progress and Achievement, Pioneer Press, Chicago, 1911.

- “The Story of the Purchase of the Logan County Courthouse and its Removal to Greenfield Village by Mr. Henry Ford, as told in the columns of the Lincoln Evening Courier, 8/19/29-10/21/29”, compiled by Thomas I. Starr, Aug 1931. Logan County Courthouse Building Files, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2010s, 19th century, 1840s, Illinois, Michigan, Dearborn, presidents, making, Logan County Courthouse, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, collections care, by Jim Johnson, Abraham Lincoln, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

In October 2017, Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation was awarded another Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) grant, allowing us to continue working to catalog, conserve, package, and rehouse over 3,000 items out of our Collections Storage Building. We've had the opportunity to work with some very interesting objects for this grant, from agricultural equipment to advertisement signs. There is a wide array of objects passing through the labs, visible to the public through the windows at the back of the museum.

In October 2017, Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation was awarded another Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) grant, allowing us to continue working to catalog, conserve, package, and rehouse over 3,000 items out of our Collections Storage Building. We've had the opportunity to work with some very interesting objects for this grant, from agricultural equipment to advertisement signs. There is a wide array of objects passing through the labs, visible to the public through the windows at the back of the museum.

This spring we treated many batteries made by Thomas Edison. Most of these originated from the late 19th century and varied in condition and composition. These early battery types consist of metal plates that were immersed in an electrolyte solution to generate electricity. The batteries themselves were stable and safe to handle because they contained no electrolyte. The batteries with unknown compositions sparked our curiosity (pun intended), since we needed to know what they were made of so that we could properly conserve them.

Sometimes while working in the lab, we need specialized equipment that we may not have on site. Fortunately, museums often work collaboratively to help each other find solutions. In this case, we collaborated with Conservation Scientist Christina Bisulca and the well-equipped analytical conservation lab at the Detroit Institute of Arts. The DIA had the right tool for the job - a high-powered optical microscope and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer. An XRF spectrometer is essential to conservators because it is used to identify metals. It uses an X-ray beam to produce enough energy to excite electrons within the atoms of metal elements. When that energy is released, a specific signal is registered within the XRF spectrometer and the metal is identified.

The DIA’s XRF spectrometer analyzing the central core of one of the batteries. (Photo courtesy of Misty Grumbley.)

At the beginning of March, we brought several batteries to test at the DIA, including an Edison-Lalande battery, a Samson battery, and an Edison S-Type battery. The Edison S-type battery was particularly interesting, since we were not able to find any similar batteries to compare it to, and could not confirm the materials used through research alone.

Continue Readingtechnology, power, Thomas Edison, Detroit Institute of Arts, collections care, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, IMLS grant, conservation, by Misty Grumbley

Emmy Award-winning The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation with Mo Rocca is a weekly celebration of the inventor’s spirit, from historic scientific pioneers throughout past centuries to the forward-looking visionaries of today. Each episode tells the dramatic stories behind the world’s greatest inventions and the perseverance, passion and price required to bring them to life.

The fourth season of The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation with Mo Rocca marks its 100th episode on April 28, 2018. We asked a few of the curators you've seen on screen and who work hard behind the scenes to share some of their favorite memories and artifacts from the show so far.

One of my favorite Innovation Nation episodes to work on featured the 1964 Moog synthesizer prototype—a singular artifact that impacted the history of electronic music. I remember being on set very early in the morning with Mo and scrambling to figure out how to play “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” on our Minimoog synthesizer in time for the cameras to roll. I think it was a success, though no record deals have arrived yet!

Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication & Information Technology

I’m so glad we opened our 1923 Canadian Pacific snowplow for the first season of Innovation Nation. Not only did it help illustrate the work required to keep a railroad operating year-round, it provided an opportunity for us to photograph the snowplow’s interior. Now everyone can share the experience through our Digital Collections!

Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

For me, nothing tops the segment on Henry Ford’s 1896 Quadricycle. Because we have an operating replica, Mo and I could experience the artifact in a way that’s different from simply looking at – or even touching – something. No doubt Henry had his frustrations building the original but, based on our ride, he had some fun along the way, too!

Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

One of my favorite moments was walking into the Lovett Hall ballroom to see Susana Hunter’s vibrant improvisational quilts spread out on the gleaming wooden floor. I had seen these quilts many times before. But in this setting, the group looked absolutely luminous—and Susana’s joyful, creative spirit shown through every quilt.

Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

quilts, quadricycle, railroads, technology, music, TV, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation

Metal, Hard Rubber, and Corrosion Products

In this blog post, conservator Louise Stewart Beck shared some incredible photographs of corrosion products that seemed to grow from the metal itself. We have found a lot of corrosion products where metal and hard rubber materials meet. In this collection, it happens frequently, and it makes sense to find these two materials so often due to the physical properties of the materials and their uses in regards to electricity.

In this blog post, conservator Louise Stewart Beck shared some incredible photographs of corrosion products that seemed to grow from the metal itself. We have found a lot of corrosion products where metal and hard rubber materials meet. In this collection, it happens frequently, and it makes sense to find these two materials so often due to the physical properties of the materials and their uses in regards to electricity.

Let’s start with the metal. Metals are strong materials, allowing the objects to withstand the working environments where they were used. Additionally, metals make great conductors, allowing the electricity to readily flow through the desired path along wires.

While metals are conductors, rubber is an insulator. This means it restricts the flow of electrons and prevents the electricity from transferring to separate entity—like a person—accidentally.

With this in mind, it makes sense that both metals and hard rubber would be found next to each other for the electrical objects to perform their function when first created. The long-term proximity of metal and hard rubber on these objects, unfortunately, also leads to active deterioration of the object. This situation is called inherent vice: The deterioration of physical objects due to the instability of the materials that make up the object.

Group of metal objects with hard rubber carrion on the surface. (Accession number 31.1217.252).

Detail of hard rubber corrosion on surface of the metal. (Accession number 31.1217.252).

When Louise and I encounter the strange corrosion products where hard rubber and metal touch, we end up removing the product of a chemical reaction occurring due to the physical properties of the two materials. If the corrosion product is only removed, it will be back in a few years because the chemical reaction has not been stopped by simply removing the corrosion. Whenever possible, a barrier is placed between the hard rubber and metal to keep them from chemically interacting with one another. Our barrier of choice is Incralac, a clear non-reactive coating. When possible, we apply the coating to the metal after separating it from the hard rubber and allow it to dry. Once dry and reassembled, the barrier layer should prevent the chemical reaction that results in the interesting corrosion growth.

Conservator Louise using a scalpel to mechanically remove the hard rubber corrosion. (Accession Number 31.1217.252).

Conservator Louise submerging metal in Incralac after removing corrosion to form a barrier layer between the metal and the hard rubber to prevent further corrosion. (Accession number 31.1217.252).

Of course, a lot of thought goes in to each treatment for each unique object, making working with this collection both challenging and rewarding. Understanding the ways objects are originally created that may cause or increase deterioration allows us in the Conservation Lab to actively work to slow this deterioration down to ensure the object can be enjoyed by visitors for years to come. Corrosion removed, waiting for the Incralac to dry. (Accession number 31.1217.252).

Corrosion removed, waiting for the Incralac to dry. (Accession number 31.1217.252).

Mallory Fellows Bower is the IMLS Conservation Specialist at The Henry Ford.

by Mallory Fellows Bower, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, collections care, conservation, IMLS grant

Lamy’s Diner Gets a Makeover

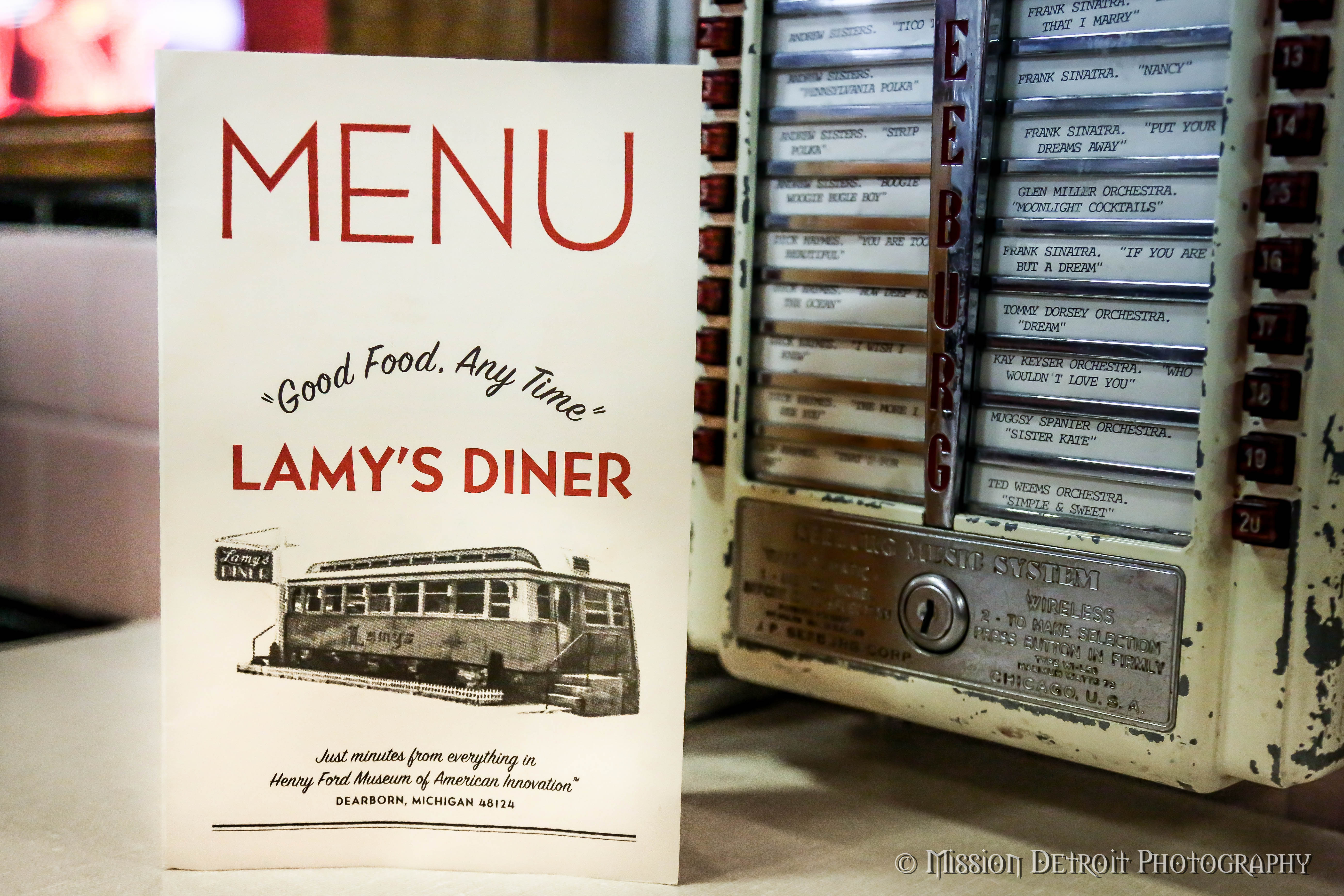

Where can you get a real diner experience, especially here in Michigan? The answer is Lamy’s Diner inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation—an actual 1946 diner brought here from Massachusetts, restored, and operating as a restaurant in the Museum since 2012.

Now Lamy’s Diner is more authentic, more immersive, and serving more delicious food than ever! What’s behind this makeover?

In 1984, the Henry Ford Museum purchased the Clovis Lamy's diner. It took a crane to lift the diner in preparation for transporting it from Hudson, Massachusetts. Once here, it was restored to its original 1946 appearance. THF 25768

Back in the 1980s, museum staff worked with diner expert Richard Gutman to track down an intact vintage diner for the new “Automobile in American Life” exhibit. Gutman not only found such a diner in Hudson, Massachusetts (moved twice from its original location in Marlborough, Massachusetts) but also helped in its restoration and in interviewing its original owner, Clovis Lamy, about his experiences running the diner and about the menu items he served.

Diners are innovative and uniquely American eating establishments. Lamy, like other World War II veterans, was lured by dreams of prosperity and the independence that came with being an entrepreneur of his own diner. As he remarked, “during the war, everyone had his dreams. I said if I got out of there alive, I would have another diner—a brand new one.”

This photograph shows Lamy's Diner on its original site in Marlborough, Massachusetts, 1946. The diner moved three times, first to Framingham, Massachusetts, next to Hudson, Massachusetts in 1949, and finally to the Henry Ford Museum in 1984. THF88966

Sure enough, when he was discharged from the army, he ordered a 40-seat, 36- by 15-foot model from the Worcester Lunch Car Company, a premier diner builder at that time. It boasted a porcelain enamel exterior, 16 built-in stools, six hardwood booths, a marble counter, and a stainless steel back bar. Lamy could choose the diner’s colors, door locations, and outside lettering. He and his wife Gertrude visited the Worcester plant once a week, eager to check on its construction.

Clovis Lamy stands behind the counter of his diner in Massachusetts. His favorite part of running a diner was talking to his customers. THF 114397

Lamy’s Diner opened for business in April 1946, in Marlborough, Massachusetts. As Lamy remembered, business was brisk:

We jammed them in here at noon—workers from the town’s shoe shops—and we had a good dinner trade too… People stopped in after the show…[and] after the bars closed, the roof would come off the place.

During the long hours of operation (the place closed at 2 a.m.), the kitchen turned out everything from scrambled eggs to meat loaf. To Clovis Lamy, there was no better place than standing behind the counter talking to people.

But the dream had its downside. The work day was long. He was seldom able to eat with his family. After moving the diner to Framingham, Massachusetts, he sold the business in 1950. The new owner moved it down the road to Hudson.

Lamy’s Diner exterior as it looked in the Museum in 1987. THF 77241

When Clovis Lamy and his wife viewed the diner at the 1987 opening for “The Automobile in American Life” exhibition, they confirmed that it looked as good as new. “Even the sign is the same,” he remarked later with a tear in his eye.

Lamy’s Diner interior as it looked in the Museum in 1987. THF 3869

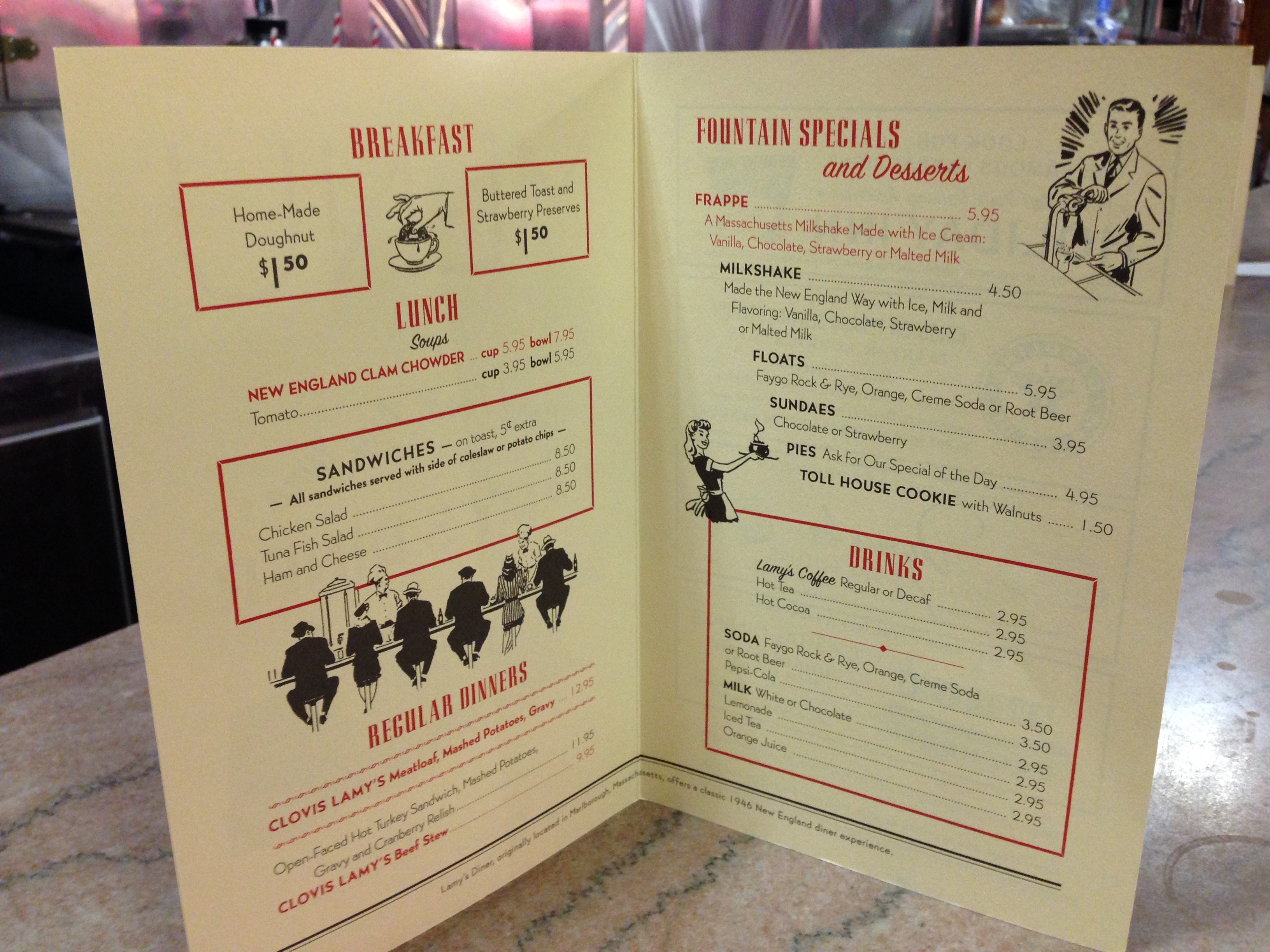

For 25 years, no food was served at Lamy’s Diner in the museum. It was interpreted as a historic structure, until the opening of the new “Driving America” exhibit in 2012, when museum staff decided to once again serve diner fare there. Delicious smells of toast and coffee wafted out of its doors, while the place hummed with activity. Museum guests sat in the booths, on stools at the counter, or at tables on the new deck with accessible seating. They could choose entrees, beverages, and desserts from a menu that was loosely inspired by diner fare of the past.

Then, in 2016, Lee Ward, the new Director of Food Service and Catering, came to me and posed the question, what if we served food and beverages at Lamy’s that more closely approximated what customers would have actually ordered here in 1946? The diner is already an authentic, immersive setting. What if we took it even further and truly transported guests to that time and place? I have always believed in the power of food to both transport guests to another era and to serve as a teaching tool to better understand the people and culture of that era. Over the years, I’ve helped create Eagle Tavern, the Cotswold Tea Experience, the Taste of History menu, the Frozen Custard Stand, and cooking programs in Greenfield Village buildings. So I excitedly responded, sure, we could certainly do that!

But, as the chefs and food service managers at The Henry Ford began to ply me with endless questions about the correct menu, recipes, and serving accoutrements for a 1946 Massachusetts diner, I realized I needed help.

Dick Gutman talking to Lamy’s staff.

Fortunately, help was forthcoming, as Richard Gutman—the diner expert who had found Lamy’s Diner for us in the 1980s—was overjoyed to return to the project and give us ideas and advice. And the 300-some diner menus he owned in his personal collection didn’t hurt either. In fact, they became our best documentation on diner foods and what they were called in 1946, as well as the graphic look of the menus.

Cookbooks of the era offered actual recipes for the dishes we saw listed on the menus, while historic images of diner interiors provided clues as to what the serving staff might wear, what kinds of dishes customers ate on, and what was displayed in the glass cases on the counter.

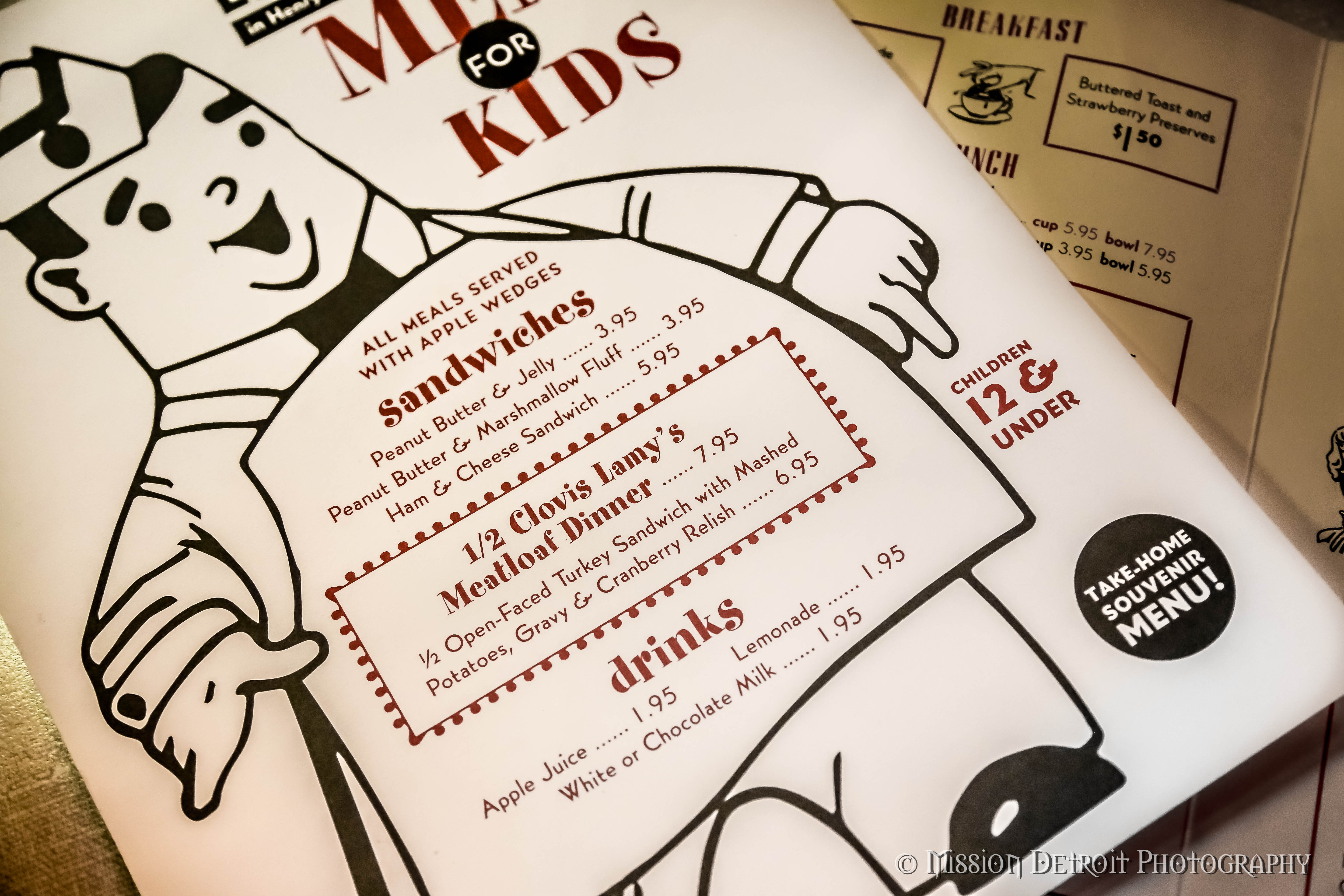

All of these are reflected in the current Lamy’s Diner experience. Here’s a glimpse of what you’ll encounter when you visit Lamy’s after its recent makeover:

New Lamy’s Diner menu, front and inside

Kids’ menu

New England Clam Chowder, a signature dish in New England diners and here at Lamy’s

Chicken salad sandwich, using a recipe from the 1947 edition of the Boston Cooking School Cookbook, a pioneering cookbook that offered practical recipes for the average housewife.

Meat loaf plate, using Clovis Lamy’s original meatloaf recipe

Milkshake, which in Massachusetts is a very refreshing drink made of milk, chocolate syrup, and sometimes crushed ice (no ice cream), shaken until it is creamy and frothy.

Toll House cookies, invented by a female chef named Ruth Graves Wakefield in 1938, at the Toll House Inn in Whitman, Massachusetts.

Peanut butter and marshmallow fluff sandwich, a New England specialty based upon Archibald Query’s original marshmallow creme invention and later called “Fluffernutter”

Prices are, by necessity, modern, but typical prices of the era can be found on the menu boards mounted up on the wall, based upon Lamy’s original menu and prices.

So, for a fun, immersive, and delicious experience, check out the makeover at Lamy’s Diner!

In Other Food News...

A Taste of History: Now featuring recipes and menu items guests might see prepared in Greenfield Village historical structures, such as Firestone Farm and Daggett Farmhouse.

Mrs. Fisher's Southern Cooking: The menu is based solely on Mrs. Fisher's 1881 cookbook or authentic recipes.

American Doghouse: New regional hot dog options are available, from the Detroit Coney and Chicago dogs to the California dog wrapped in bacon and avocado, tomato and arugula.

Donna R. Braden, Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford and author of this blog post, has decided that her new favorite drink is the refreshing Massachusetts version (without ice cream) of the chocolate milkshake. She thanks Richard Gutman and Lee Ward for their enthusiasm and support in making this makeover possible.

Massachusetts, 21st century, 2010s, 20th century, 1980s, 1940s, restaurants, Henry Ford Museum, food, Driving America, diners, by Donna R. Braden, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Mentoring Youth at The Henry Ford

In 1990, a partnership was formed between The Henry Ford and Wayne-Westland Community Schools that would revolutionize the way The Henry Ford looked at community outreach. High School students would spend the first half of their days in the classroom, then be transported to The Henry Ford in taxis where they would spend the remainder of their school day working alongside full-time employees learning vital work skills, forming positive relationships, and creating memories that would last a lifetime.

Twenty-six years later the foundation of the program remains the same. Students from the district continue to make the daily commute to The Henry Ford (although in school buses rather than taxis) where they work in placements ranging from the William Ford Barn, Firestone Farm, Institutional Advancement, banquet kitchens and restaurants, and the Ford Rouge Factory Tour. They now have the opportunity to obtain additional academic credits by completing online courses, and participate in community engagement by practicing service learning with second-grade classrooms at an elementary school in the district on a weekly basis. Service learning allows our students to give back to their communities, and realize the impact they can have on the lives of others.

The students we serve have been identified by their counselors and principals for being at-risk for graduation. Academic struggles usually stem from a multitude of underlying issues such as an unstable home life, mental/physical health issues, or perhaps just lacking a sense of belonging in this world. People learn in different ways and normal schooling isn’t for everyone; the Youth Mentorship Program provides an atmosphere where students can succeed in an environment different from the traditional classroom.

The Youth Mentorship Program is a source of pride here at The Henry Ford. It’s one of the clearest ways we inspire people to learn from these traditions to help shape a better future, as our mission statement proudly states. Unlike most programs at The Henry Ford, the Youth Mentorship Program caters to a smaller group; approximately 12-15 students per semester. The students have the ability to participate in the YMP for a semester or longer, depending on what their schedule allows. Although small in numbers, we believe the YMP is a program that runs ‘an inch wide and a mile deep.’ Although we have a great desire to reach all youth in need in our community, small group size allows for more one-on-one opportunity as well as an overall intimate atmosphere. A quote we hear amongst our students year after year is how the YMP is truly like a family.

It’s incredibly inspiring to watch these students learn their place in the world and become good and successful citizens of their community. Whether it’s passing classes and earning credits, serving The Henry Ford’s guests in a banquet kitchen or restaurant, shearing sheep at Firestone Farm, or walking across a stage to grab their high school diplomas, the Youth Mentorship Program opens the eyes of students to opportunities they may never imagined with overwhelming cheers of support. It truly has deep and lasting impact on the students it serves each semester, as well as the students’ families, The Henry Ford staff, and the Wayne-Westland community.

Help us continue making our community impact by making a donation to the Youth Mentorship Program this Giving Tuesday. How can your donation help?

- $10 can provide a semester's worth of school supplies for a student

- $30 will help uniform one student

- $50 supplies a month's worth of meals for a student

- $200 pays for one online course for a student to complete to earn credit

- $2,500 provides transportation for one student for the year

Continue Reading

Michigan, philanthropy, #GivingTuesday, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, educational resources, education, school, childhood, by Emily Koch